How Invention Begins preface and ch. 1

In this book he asks the question: "How does invention (of new technologies) work?"

- prior knowledge

- individual creativity

- does the invention meet a need?

- why are things fairly often invented by different people at the same time?

- what is necessary for a new technology to be accepted?

Definitions:

We sometimes today use "technology" to mean computers. But for the purposes of this course we need a much broader definition of technology.

Before the rise of science-based engineering in the late 19th century, what we would today call engineering was done by craftspeople with little education. They used hands-on knowledge and ingenuity, not the scientific theories or mathematical analysis that were developed by scientists. Craftspeople learned from experience, not from systematic, objective experimentation.

Hands-on knowledge is knowledge that one has picked up, makes sense, and happens to work. It has not been gained through systematic reasoning and experimentation designed to isolate the variables established in scientific laws, and therefore it is not scientific knowledge.

Bear in mind

here that

historians want to understand how people acted based on what

they

understood at the time. We can today give scientific

explanations

about why something works, but if they didn't have a

scientific

explanation back then I wouldn't consider that that person

in the past

used science.

The dictionary definitions of science and technology are often dreadful. (You can find an on-line dictionaries to search at: dictionary.com or go straight to the OED through the Clemson library. For example, the American Heritage Dictionary, Office Edition, definitions:

Technology= 1. The application of science, esp. in industry or commerce. 2. The scientific materials and methods then used.

I think this is a terrible definition--technology is much more than just the application of science. Much modern technology may involve the application of formal science, but before the industrial revolution technology did not grow from science (see Florman chs. 3 and 4). Scientists in the 18th and first half of the 19th century were coming up with new theories of chemistry and physics, but engineers were still improving technology by trial and error, not using the theories of the scientists.

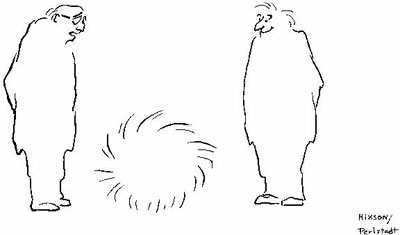

“Obviously, your invention works in practice,

but

there’s one insurmountable problem:

It will never work in theory.”

The American Heritage Dictionary definition of technology makes more sense when you see their definition of science:

Science= 1. The observation, identification, description, experimental investigation, and theoretical explanation of phenomena. 2. Methodological activity, discipline, or study. 3. An activity regarded as requiring study and method. 4. Knowledge gained through experience.

Now that really is a terrible definition (if you don't believe me ask a scientist). By #3 you could certainly say that theology or art was a form of science, and many people would say that by #4 their belief in God was based on science. I think you need to define science much more narrowly (#1 might be ok if you specified that a science must have all these characteristics). Science is what scientists do, it does not include all forms of knowledge about nature.

Here are some better definitions:

An old-fashioned definition that is still useful: Tredgold, 1828: "Engineering is the art of directing the great sources of power in nature for the use and convenience of man." (Florman p. 66.)

My own definitions:

Technology= ideas and techniques for manipulating (or modifying) the environment.

Science= knowledge about the physical world that is generalized (scientific laws--not individual observations), mathematical (or at least predictive), and based on systematic experiment or observation (it must be all of the above to count as science).

I am attempting

to

define science in a way that is limited to what scientists

do.

There are other ways of knowing about nature, but I would

call them

unscientific. For another approach see: What

Is

Science

Most important

for our

purposes--some technology is based on science and some is

not

(craft-based)

Lienard uses the story of finding the body of a man from over 5,000 years ago to ask us to think about the limits of history

Historians ask questions they might be able to answer

they simplify the story, though not as much as sociologists or political scientists do

as they go deeper they are fascinated by the details that aren't what we expected

they want to see the complexity of people, rather than making them heroes

Elementary school history tends to look for heroes, but now we are interested in how it is more complicated than that

There were usually (always?) many people involved in what one person gets credit for